The Australian Asphalt Pavement Association: re-frame the roads conversation

First published in Road Surface Technology 2015 as The Australian Asphalt Pavement Association wants to re-frame the roads conversation

“Innovation driving value” was the main theme at this year’s Australian Asphalt Pavement Association (AAPA) conference, along with communication. Speaker after speaker emphasised the need to improve the way our industry communicates with the public and with government, especially if it wants to realise the huge benefits of innovation. Get it wrong and your country as well as your national infrastructure will go into decline, the conference was warned. Callum Rhodes reports.

“Innovation driving value” was the main theme at this year’s Australian Asphalt Pavement Association (AAPA) conference, along with communication. Speaker after speaker emphasised the need to improve the way our industry communicates with the public and with government, especially if it wants to realise the huge benefits of innovation. Get it wrong and your country as well as your national infrastructure will go into decline, the conference was warned. Callum Rhodes reports.

It was keynote speaker Dr Keith Suter, a strategic consultant and political commentator, who caught the mood of the conference. Innovation is now vital to the very survival of Australia itself he said. “It is not written in the sky that any country is destined to survive. Yes, Australia is very rich and we are doing well at the moment, but there is no guarantee that we will survive. There are more dead civilisations than currently flourishing ones.”

Be careful he said: Australia is a country in decline. It was the world’s richest country in per capita terms in 1900, but it has slipped down the list “considerably” in the last 100 years. According to Suter, the problem is that Australia remains a commodity-driven economy and it is resting on its laurels. The country is failing to invest properly in research and development and 98% of the technology used by Australian business today originates from other countries. Talented young Australians now look abroad for better career opportunities.

Complacency has become a threat to Australia’s well-being, Suter argued. “No society has ever developed without improving its infrastructure. Often (a country’s) residual infrastructure is a lasting physical monument to what civilisation has achieved.” A significant part of the solution, he suggested, was to reframe the way engineers and experts communicate with the public and with government: see our “Sell the sizzle” box below.

Emerging innovations are going to have a dramatic impact. For instance: driverless cars. Road crashes kill 1.2 million people around the world each year. In his presentation on the Queensland Department of Transportation and Main Roads (TMR) strategy for delivering safe roads, TMR deputy director general Mike Stapleton revealed that crashes cost the Australian economy around A$27 billion each year. And because the majority of crashes are caused by human error and extreme behaviour, the impact of removing the driver from the equation will be huge.

Innovations don’t need to be as revolutionary as autonomous vehicles, however. Stapleton showed the long term reduction in road fatalities in Queensland resulting from road safety treatment improvements as simple as widening the centre line on the state’s notorious Bruce Highway. This simple move reduced the number of casualties resulting from head-on collisions and improved speed limit compliance by narrowing the driving lane.

The AAPA also took a look at the US where, according to Auburn University’s Dr David Timm, the national road network has recently received a mediocre “D” rating from the American Society for Civil Engineers. Things are not looking good: congestion on US roads now costs the country’s economy US$101 billion a year in wasted time and fuel. And it is not a small problem: America’s highway network represents around 10% of the entirety of the world’s road system.

Timm, who works closely with the National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT), a test track for road technology in Alabama, said “much of our infrastructure was designed for a 20-year lifespan, (after which) they’re meant to have a terminal amount of cracking and a terminal amount of rutting … and yet we’re expecting them to last much longer than that.”

Suter, the problem is that Australia remains a commodity-driven economy and it is resting on its laurels. The country is failing to invest properly in research and development and 98% of the technology used by Australian business today originates from other countries. Talented young Australians now look abroad for better career opportunities.

Complacency has become a threat to Australia’s well-being, Suter argued. “No society has ever developed without improving its infrastructure. Often (a country’s) residual infrastructure is a lasting physical monument to what civilisation has achieved.” A significant part of the solution, he suggested, was to reframe the way engineers and experts communicate with the public and with government: see our “Sell the sizzle” box below.

Emerging innovations are going to have a dramatic impact. For instance: driverless cars. Road crashes kill 1.2 million people around the world each year. In his presentation on the Queensland Department of Transportation and Main Roads (TMR) strategy for delivering safe roads, TMR deputy director general Mike Stapleton revealed that crashes cost the Australian economy around A$27 billion each year. And because the majority of crashes are caused by human error and extreme behaviour, the impact of removing the driver from the equation will be huge.

Left-right – Thierry Defréne (chiefexecutive of Colas Australia, AAPA oard member),Michael Caltabiano, Tony Aloisio, Neil Scales:smoother roads means an efficient Australia

Left-right – Thierry Defréne (chiefexecutive of Colas Australia, AAPA oard member),Michael Caltabiano, Tony Aloisio, Neil Scales:smoother roads means an efficient AustraliaInnovations don’t need to be as revolutionary as autonomous vehicles, however. Stapleton showed the long term reduction in road fatalities in Queensland resulting from road safety treatment improvements as simple as widening the centre line on the state’s notorious Bruce Highway. This simple move reduced the number of casualties resulting from head-on collisions and improved speed limit compliance by narrowing the driving lane.

The AAPA also took a look at the US where, according to Auburn University’s Dr David Timm, the national road network has recently received a mediocre “D” rating from the American Society for Civil Engineers. Things are not looking good: congestion on US roads now costs the country’s economy US$101 billion a year in wasted time and fuel. And it is not a small problem: America’s highway network represents around 10% of the entirety of the world’s road system.

Timm, who works closely with the National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT), a test track for road technology in Alabama, said “much of our infrastructure was designed for a 20-year lifespan, (after which) they’re meant to have a terminal amount of cracking and a terminal amount of rutting … and yet we’re expecting them to last much longer than that.”

The cost of bringing that infrastructure up to an ‘A’ rating would be US$170 billion a year, almost double the current funding level according to Timm – an astronomical cost for rehabilitation. Compared to digging up and rebuilding roads, milling and resurfacing a perpetual pavement is far more economical. “If we can get all our road infrastructure to the point where all we’re having to do is a mill and inlay, and the rest of the pavement foundation is intact, that’s a more sustainable model for us,” Timm said.

AAPA CEO Mike Caltabiano took a different line, underscoring the importance of perpetual pavements. They represent “a completely different design approach and a change in philosophy,” he said, “to deliver the pavements that the community expects us to deliver”. The public, he argued, are increasingly intolerant of massive end-of-life interventions to rehabilitate ageing roads.

Good ideas need to be put into action though. Whether they are perpetual pavements or solar roads (see “The road of the future” box below), the conference endorsed the need for innovation to be backed up by implementation. As Dr John Harvey, from the University of California Davis, put it: “Without implementation, innovation has a benefit to cost ratio of zero.”

Some decision makers have already recognised this. TMR director general Neil Scales outlined a new process in the department for advancing engineering innovations from ideas to reality.

“We’ve got to make sure we cut the pilot off at the right point,” he said. “Then we can see what we learned, what was important, and what can be applied. I’d rather try something and fail quickly than not try at all. One of the things I say to my people is, you’ve got to make decisions. This is the only way we’re going to advance the cause of engineering and of pavement technology.”

Problems with funding, and the inconvenience of major road works mean that the road surface technology industry needs to improve the way in which it communicates with stakeholders, many speakers admitted. One of the primary issues identified was the conflict between the public’s expectations of roads – that they are smooth, safe and well-maintained – and the public’s unwillingness to brook financial or physical inconvenience to realise those expectations.

According to David Newcomb, a senior research scientist at Texas A&M’s Texas Transportation Institute, “back in the days when pavements weren’t considered a natural geological formation, it was easier to get funding for them. Nowadays, people don’t seem to understand that just because a road’s always been there doesn’t mean it remain in place.”

Convincing the public that, on the contrary, roads require continual investment and maintenance, is a matter of shifting the terms that the industry speaks in, according to AAPA’s Mike Caltabiano. “When we talk about smoother safer roads, we talk about productivity and economic growth, and making our country more efficient. That’s the language that our state road authorities and our federal government understand. When we talk about pavement engineering, the structure, the overlay, the asphalt mix design, people’s eyes glaze over. For us as an industry, that’s part of the change that we have to engage in. We have to speak a different language.”

AAPA chairman Tony Aloisio summed it all up by saying that even though modern society is aware of digital connections, the internet and social media, it is the “physical connections between our communities are what have driven and forged civilised societies for thousands of years.” Europe’s Roman roads knitted together a wide and disparate empire and they remains a legacy some 2000 years later. “Our legacy should be keeping communities connected, safely and efficiently,” he said.

Sell the sizzle

Infrastructure is a neglected topic in Australia, according to Dr Keith Suter. Infrastructure experts must change the way they communicate, or “reframe” the national conversation, in order to bring the topic to mainstream attention.

“If you want to get people to pay attention to what you’re about, you add ‘security’ to your noun,” Suter said in Tuesday’s keynote. “Water security, pension security, health security, food security. That’s a way that we might be able to get some political attention on this.”

In fact, this was how funding for the US interstate highway system was secured in the 1950s. Suter described the system as one of the most ambitious and consequential engineering projects in history, but then-President Dwight Eisenhower was only able to convince Congress to approve it by painting it as a security measure against a potential Soviet invasion.

Eisenhower’s argument illustrates the primary obstacle to long term infrastructure thinking: there are two modes of thinking at work. Engineers and scientists exist in a rational world in which the importance of infrastructure is self-evident, but politicians, the media and the wider public exist in another, different world.

This other world is frequently reluctant to make changes, according to Suter, but energising the political debate on infrastructure will require engineers and others in the industry to reframe the conversation. Taking the concept of infrastructure security a step further, Suter suggested a campaign to position roads and infrastructure as a human right, a method of maximising wealth and improving social cohesion as well as enhancing national security.

“We are living in the attention economy, whereby people are competing for attention,” he said. “What you’ve got to do is sell the sizzle, and not the sausage. This industry is on the frontline of Australia’s national defence, and the general public ought to know.”

The road of the future

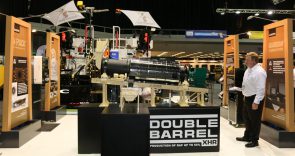

Departing from the day-to-day practicalities of pavement engineering, Colas’ director for technology, research and development Philippe Raffin gave an overview of technologies that may come to define the roads of the future – from imminent realities to blue sky imaginings.

In Raffin’s view, innovation must be backed up by both technical readiness and business readiness. Otherwise, it is merely research and development.

“Whatever the level of technology reached by R&D, we have to be sure it can be developed, it can be sold, taking into account equipment, environmental issues, health and safety and marketing,” Raffin said. “If you don’t have those extra things, R&D is useless. Innovation is the whole chain of all that knowledge and skill.”

The European Union has recognised infrastructure development as an answer to some of the impending challenges facing the world.

“The road has to contribute to all these challenges,” Raffin said. With that in mind, he offered a handful of component technologies as examples of the ‘road of the future’. Among these were miniaturised traffic sensors; sensors embedded in roads to measure pavement performance and assist in asset management; electrical induction to power vehicles such as buses; and piezoelectric energy generation.Raffin finished his presentation with a teaser for a Colas effort to integrate photovoltaic technology into existing road surfaces – a “solar road”.

“The solar road is, first, a road,” he said. “It must be flexible, adapted to traffic and climate, comfortable, with good skid resistance. But it’s also a photovoltaic panel, with translucent aggregates and binders. It has to be compatible with electricity networks, and address electrical safety concerns.”

Companies in this article

Australian Asphalt Pavement Association